Should trees have rights?

The UK government last month dismissed the idea that nature could have rights.

“The UK’s firm position is that rights can only be held by legal entities with a legal personality. We do not accept that rights can be applied to nature or Mother Earth. While we recognise that others do, it is a fundamental principle for the UK and one from which we cannot deviate.”

So said the (unnamed) UK delegate to the UN environment assembly in Nairobi.

He (he was identified as such) uses strong language. It is a ‘fundamental principle for the UK’. It’s not a fundamental principle that I am aware of. He says it is one from ‘which we cannot deviate.’ (My emphasis). Why not? Perhaps we need to be asking the government.

Other countries have decided that they CAN move in the direction of rights for nature. Ecuador, Bolivia and Uganda are countries which have the rights of nature in their constitution or laws. This doesn’t necessarily offer nature protection, as, for example, there is continued deforestation and drilling for oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon, but it is a start.

There are grassroots movements in the UK campaigning for the rights of nature. Love our Ouse in East Sussex is campaigning for Rights of Rivers. Lewes District Council was the first council to pass a motion acknowledging the rights of river - a charter is now being developed which will be sent to the council to endorse.

In the Garden Futures exhibition at the Design Museum in Helsinki, there were a number of examples of initiatives specifically related to the rights of trees. In his book We Have Never Been Modern, the philosopher Bruno Latour argued for granting political rights to “non-humans, to quasi-humans, to hybrids.” In her collage, The Parliament of Plants, Céline Baumann shows non-human species having their say in a green democracy, where all decisions would be based on the public good, on mutual care and support.

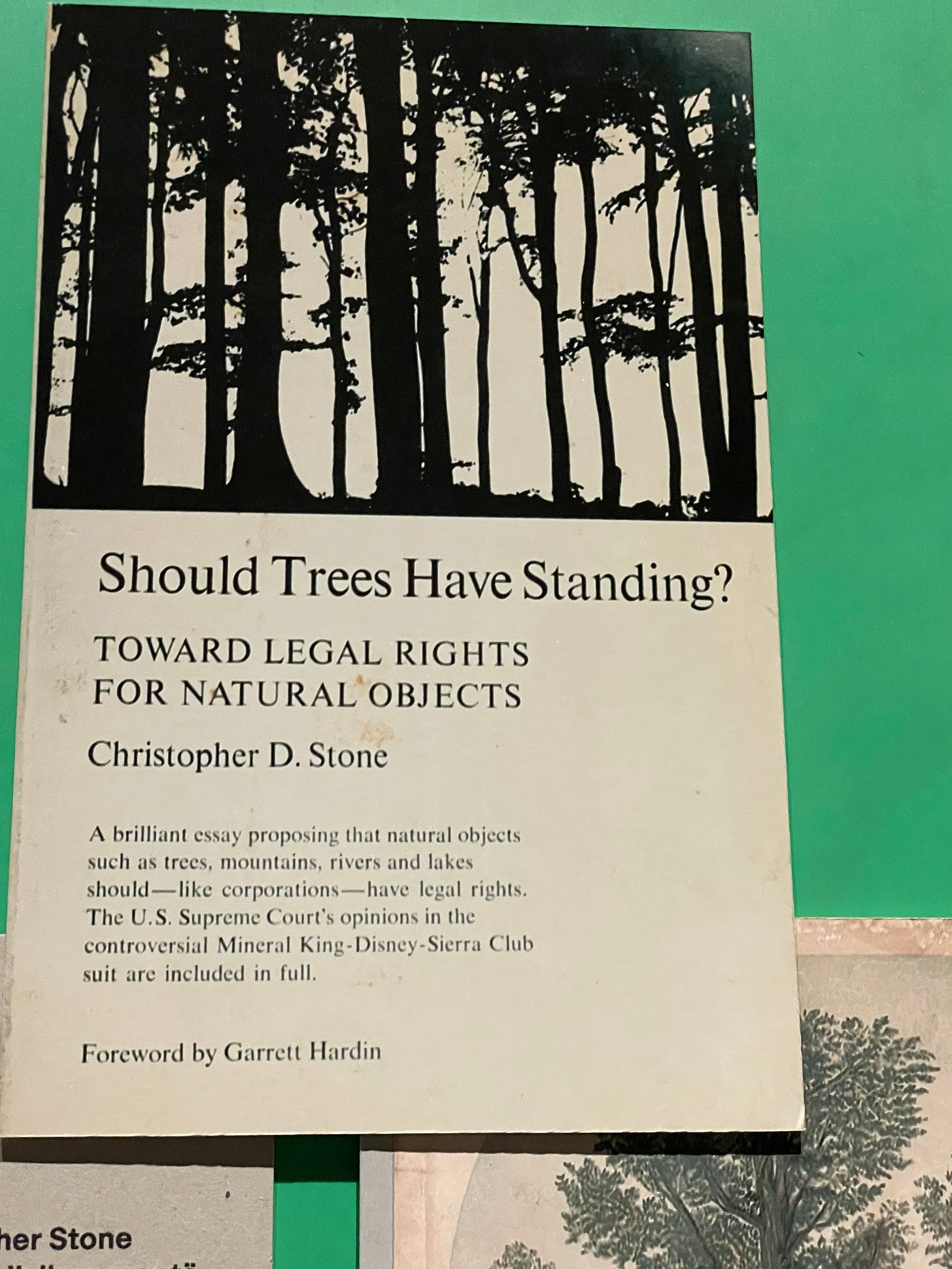

Also highlighted in the exhibition was the lawyer Christopher Stone’s essay from 1972, ‘Should Trees have Standing?’ which was the beginning of the rights of nature movement.

The focus of the essay was on the extension of ‘legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called ‘natural objects’ in the environment.’ Yet, in the final paragraph, he goes further saying:

“What is needed is a radical new theory or myth — felt as well as intellectualized — of man’s relationships to the rest of nature.”

This articulates the necessity to go beyond the law - and into the lore - addressing the interconnection of humanity with nature.

It is an aspect of the discussion around this issue that Anna Grear has also articulated. She has written:

“We need to get rid of the notion of a rights-bearer who is an active, wilful human subject, set against a passive, acted-upon, nonhuman object. The law, in short, needs to develop a new framework in which the human is entangled and thrown in the midst of a lively materiality—rather than assumed to be the masterful, knowing centre, or the pivot around which everything else turns.”

There is an indigenous-led movement in Ecuador which is calling for greater recognition of the rights of nature - and the rights of indigenous people to live in a way that is alignment with their worldview. The Sarayaku people have proposed the concept of ‘Kawsak Sacha’ or Living Forest. In an interview, José Gualinga Montvalo explained it like this:

“What we propose to humanity, to citizens, is to understand that we are nature, nature is itself alive and is part of us, and we are part of it. Everything we call nature, the lagoons, the trees, the marshes, the dens, the burrows, everything is interconnected. And we are interconnected, our ancestors, our parents, our grandparents, we are all interconnected. This is the Kawsak Sacha, it is the jungle, it is the forest that is alive.”

Through the Kawsak Sacha proposal, the Sarayaku people are calling for the recognition of indigenous governance in these ‘territories of life’. The legal rights of nature are important. But what is perhaps more fundamental for the long-term is the recognition of our interconnection as contained in the concept of Kawsak Sacha. There’s clearly a long way to go in the UK and elsewhere, but we can start with the big dream in mind.